How Bright Light Therapy Helps with Low Mood, Sleep Problems and Jet Lag

Last Revised November 2019

How Bright Light Therapy Helps with Low Mood, Sleep Problems and Jet Lag

By Daniel F. Kripke, M.D.

Last Revised November 2019

Advanced and Delayed Sleep Phase Treated With Bright Light

Let me explain about body clocks. We really do have 24-hour clocks inside our bodies. The main body clock is in the brain in a little area called the suprachiasmatic nucleus, smaller than a grain of rice. As the name implies, the suprachiasmatic nucleus lies in the hypothalamus just above (supra) to the optic chiasm – that is, above the place behind the eyes where the nerves from the eyes cross. The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) receives nerve impulses from those optic nerves. Basically, bright light influences the suprachiasmatic nucleus clock to keep our bodies set to the correct body time. Of course, today, modern digital watches rarely need resetting, but our body clocks can run a bit too fast or too slow like mechanical watches did in the good old days. Thousands of years ago when humans were sleeping outside, the light of dawn probably set the suprachiasmatic nucleus each morning, something like how great grandfather used to set his pocket watch every morning by the time broadcast on the radio. The light just before sunset probably set our body clocks also, to keep them very nicely in time. If great grandfather’s watch was reset every day, running a little fast or slow never got to be much of a problem. If we are outdoors at dawn and sunset, our body clocks do not cause much problem either, because the light keeps the time set well enough.

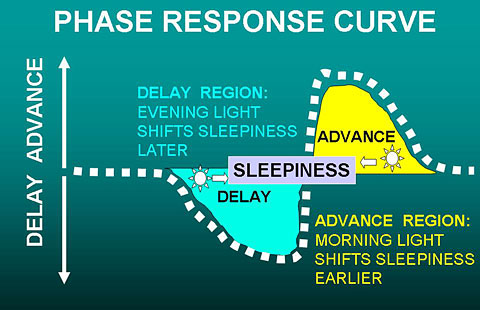

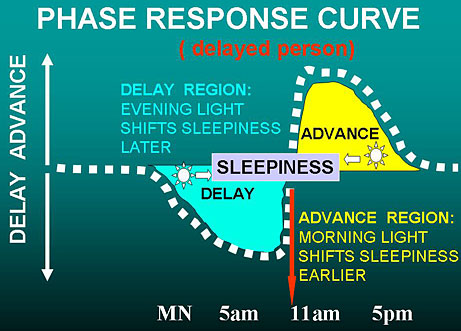

The figure above illustrates the human phase response curve.[75] When a person’s sleep has a normal relationship to the circadian clock system, light exposures from just before the time of falling asleep until past the middle of the night causes the body clock (and the nightly time of sleepiness) to delay later, as shown in light blue. Bright light in the last couple hours of sleep causes the clock (and the time of sleepiness) to advance – that is, to shift earlier, as shown in yellow. Light in the middle of the wake period, e.g., the afternoon sun, has little or no effect on the timing of the body clock.

This is exactly the same mechanism that sets the body clock in a rooster, so it knows when to crow in the morning. In fact, light sets the body clocks of the birds of the air like larks and owls and the beasts of the field, like cows and horses, lions and lambs. Light also sets the body clocks of flowers and trees. It is the natural way.

Our human body clocks do sometimes tend to run too fast or too slow, and if we are not outdoors at dawn and dusk for long enough, the timing of our body clocks can get to be a problem. In fact, there are two possible kinds of problem: the problem when the body clock is running too fast and the problem when the body clock is running too slow. Let us discuss each of these common problems.

6.A. Advanced sleep phase

When the body clock seems to run too fast, it gets ahead of the day, and sends its signals to the body too early. Then we say the timing of the body clock is advanced over what it should be (or the phase is advanced, to use a mathematical term). The main symptoms of advanced sleep phase are 1) falling asleep too early, and 2) waking up too early. People with an advanced sleep phase typically nod off in the evening reading or watching television – or even talking to the family. They may fall asleep before they go to bed. Sometimes they have to wake up to go to bed and turn off the light. Trouble paying attention to reading, homework, and favorite television shows is a problem for them in the evening. A more dangerous problem is falling asleep behind the wheel of a car in the evening. Later in the night, the person with advanced sleep phase wakes up too early. Their internal alarm clocks may wake them up at 3 am or 4 am or 5 am, long before the rooster crows, and they become distressed, because they would like to sleep later. For some folks, there isn’t much fun to be had at 4 in the morning, when everyone else is asleep.

Also, if the person with advanced sleep phase has somehow managed to stay up to a socially compatible bedtime, there may not be enough time before 3–5 am awakenings to get enough sleep. People with advanced sleep phase may typically feel most energetic in the morning and least energetic in the evening. Such a person is commonly called “a morning person” and displays “morningness” behavior.

To some extent advanced sleep phase arises from conflicts between social patterns and natural biology. Two hundred years ago, when most Americans lived on farms and there was little artificial lighting besides candles, it may have been customary to fall asleep at 8 or 9 pm and to awaken at 4 or 5 am to milk the cows, feed the chickens, and so forth. The life style of farm animals is in synchrony with the natural light cycle, so many animals get half of their sleep before midnight and have half of their waking hours before noon. People had somewhat similar habits. In a 21st century society, we like to stay up for prime time TV and The Late Show. Currently, many people do not start working before 9 am. In this social context, the sleep patterns of two hundred years ago may be perceived as a sleep disorder. Advanced sleep phase is often merely an inadaptability of natural biology to unnatural social customs.

Advanced sleep phase seems to be much more common as people live beyond 60 years of age into their 70s, and 80s. One theory for which there is some laboratory evidence is that our body clocks speed up as we age, even though most body processes are slowing down. A body clock which runs too fast tends to very gradually become advanced. Deterioration of vision may be a factor. As the lenses of our eyes become cloudy and thicken into cataracts, we see “as through a glass, darkly,” so that much less light strikes the retina of our eyes. With the eyes’ remarkable ability to adapt to changes in lighting, we may not realize the clouding of the lenses until they are shadowing almost 99% of the light falling on the corneas. Older eyes also have smaller pupils, which let in less light, like the higher f stops of a camera. Finally, glaucoma, macular degeneration and other retinal problems may impair the eyes’ light sensing mechanisms. All of these eye problems might cause elderly people to have a body clock poorly adjusted to afternoon-evening indoor lighting unless they receive extra light.

Advanced sleep phase seems to be more common among elderly women. We do not know why, but several studies have shown that among people of retirement age, the body clocks of U.S. women are set, on average, about an hour earlier than those of men. It is as if the internal alarm clocks of retired women are set to awaken them an hour earlier than those of their husbands. We do not know if this is a major factor which makes insomnia more common among elderly women, especially after menopause, but in most studies women have complained of insomnia much more than men do. A separate factor is though many doctors believe that the hot flashes and sleep disturbance of menopause go away after a few years, I think these symptoms often persist throughout the rest of life, unless the woman takes estrogen hormone replacement.

To inform our body clocks that sunset is undesirably early to become sleepy in our social organization, we must put enough evening light before our eyes for the body clock to react as if it were still day. Since rural electrification brought electric light to every home, it has become possible to light up our homes quite brightly long after the sun goes down. Lighting fixtures become more efficient year by year, so it is even easier to light up a home today than it was twenty or thirty years ago. The great enemy of good lighting seems to have become television. As the channels multiply, people watch more and more television or computer screens, which often are equally dim. Technologists tell us that a wedding of televisions, computers, and telephones is on the way, when life may be built around such screens. Because TV screens have not really been very bright, many people watch in rather dark rooms. Possibly, the larger, brighter TVs being sold in the last couple of years will help with this problem. In actual measurements of people from 60–79 years of age done over 20 years ago, we have found half of elderly people were spending the evening in less than 31 lux.[76] About 10% were spending the evening (probably watching television) in about 1 lux – about the same as sitting outdoors in moonlight! It is not hard to understand that the dim lighting of some TV rooms and living rooms is insufficient to make the body clock react as if it were day. Such dim evening light may result in an advanced sleep phase.

Solving advanced sleep phase is very simple for some people. Often, all that is needed is a brighter lamp by the TV chair. The most convenient lighting by a TV chair might be a fluorescent or LED column lamp or torchiere (a tall lamp like a torch).

In the past, I recommended a popular style of halogen-bulb “torchiere” lamp which bounces light indirectly off of a white ceiling and really lights up a room. Over 40 million of these halogen torchieres have been sold in the U.S. as the price kept coming down and down. There is no special advantage of the halogen lamps, except that they were extremely inexpensive and they have a fashionable appearance. Actually, the halogen lamps were inefficient for two reasons. First, halogen (and other) incandescent bulbs intrinsically use far more electricity than fluorescents of the same brightness. Fluorescents produce more light per watt. A 50-watt fluorescent and a 300-watt halogen are roughly equivalent. The halogen bulb produces a bigger electric bill. Second, the halogen’s very bright point of light and ultra-violet content might make it risky to look at 300-watt halogen light directly – something I never recommend. This is why the 300-watt halogen lamps are generally designed as indirect lighting. Because halogen torchiere light has to be bounced off the ceiling, indirect lighting is much less efficient than a fluorescent with diffuser that can be viewed directly. Another problem is that the 300-watt halogen bulbs get so hot that they can cause severe burns or set draperies or other objects which might touch them on fire. Over a hundred fires and several deaths have been reported due to halogen torchieres, but this is not a great risk considering over 40 million sold. Finally, the halogen bulbs burn out quickly and are difficult and somewhat expensive to replace.

Fortunately, fluorescent torchiere lamps are now widely available. A 50-watt fluorescent is roughly equivalent to a 300-watt halogen torchiere. The fluorescents will solve the safety problem and have superior energy efficiency. Fluorescent bulbs last much longer. LED lamps will have even better energy efficiency and longer life than fluorescents. Despite a higher initial cost, over several years, fluorescent and LED lamps will lower the electric bill enough to be less expensive in the long run. Because much of the torchiere light is indirect, a torchiere lamp may only produce 200–300 lux at eye level. For counteracting advanced sleep phase in the evening, a bluish-white “cool white” light is likely to work better than a “warm-white” light of the same electric consumption and brightness. That is, a cool-white or bluish-white bulb with “color temperature” rated above 5,000 K (even as much as 17,000 K) is likely to work better than one below 3,000 K.

The fluorescent light boxes which were discussed for treating depression can produce 10 to 30 times the lux at the eye as a torchiere of similar or greater wattage bouncing off the ceiling, because one can look directly at a light box placed close to the eyes. Nevertheless, torchiere lamps often seem to produce sufficient light for a TV room, a computer room, or other parts of the house. After all, 200–300 lux is about 10 times as much as the 31 lux which was our middle measurement of evening lighting for elderly people. I have seen several patients who have largely resolved a nagging advanced sleep phase problem with a simple torchiere lamp. There are probably many other ways of lighting a TV room that would work as well or better – I simply have not had as much experience with other lighting styles.

For advanced sleep phase, the time to use the right light is for 1–3 hours late in the evening, often when a person is sitting in a chair reading or watching TV (during dinner sometimes also works). It probably will not make much difference if a person gets up and down from the chair near the light, as long as the light is experienced much of the time. If a person does not stay in one room most of the evening, it may be necessary to brighten up more than one room. Some people need a longer exposure than others, depending both on the brightness of the lighting and on individual factors. The later in the evening that the bright light is used, the more powerful will be its benefit for advanced sleep phase. However, some people will find that they should dim down their lighting for about one hour before they wish to go to bed, to avoid overdosing and causing trouble with falling asleep.

A person with advanced sleep phase might begin to feel some benefit after using brighter evening light every night for a week, but it might take a month or two before the maximum benefit is reached, especially because it takes some time to restore good sleep habits. This treatment does not work unless the evening light is turned on at full brightness: I advise against using dimmers. Once the problem is under control and the body clock has readjusted, a person with advanced sleep phase can often afford to skip bright evening light on special evenings when they entertain or go out. Nevertheless, usage of brighter light in the evening probably needs to become a life-long habit. A person who benefits from bright evening light will often relapse within a month after skipping the bright light too often.

An interesting problem with bright evening light occurs when a spouse or other housemate has a different sort of body clock, possibly even a delayed sleep phase (see below). Bright evening light which is good for one person may be too much for another. This can usually be adjusted simply by arranging the placement of the lighting within the room, so that the person needing the bright light is in a brighter area than the person who does not need it. Couples have told me, however, that treating one spouse sometimes helps the other also! It all depends on the ways in which people are similar or different.

People with advanced sleep phase should avoid very bright light early in the morning, because morning light has a harmful effect for people whose body clock is already too advanced. Sometimes, walking or running outdoors soon after dawn or a long drive to work in the morning is a problem making advanced sleep phase worse. A person with advanced sleep phase might be wise to wear blue-blocking sunglasses when outdoors between the time when the sun comes up and noon. Such sunglasses have a particular orange color which filters out the blue light that is most likely to cause phase advance.

6.B. Advanced sleep phase and depression

There are two conditions which typically cause early awakening: advanced sleep phase and endogenous depression. “Endogenous” depression means the kind of melancholic mood which seems to come from inside the body and less from psychological stresses. There seems to be some relationship between advanced sleep phase and depression, particularly in middle age and beyond (though there are also many depressed people who are delayed). Some of my patients with advanced sleep phase problems likewise also seem a bit depressed, so it is difficult to distinguish the two conditions. Bright light in the evening seems to work both for advanced sleep phase and for depression with early awakening, so sometimes it may not be too important to distinguish which condition a person might have (or perhaps a person suffers both).

Nevertheless, if a depression is serious enough to keep you from your normal occupations and pleasures or to cause weight loss, guilt, thoughts of death, or other serious distress, let me repeat that you should talk it over with your doctor. For serious depressions, light treatment should often be combined with the treatments like anti-depressant drugs and counseling. Lithium may have some beneficial effect for advanced sleep phase. Moreover, for more serious depression, I often prefer one of the powerful fluorescent or LED light boxes to the torchiere lamps, since the torchiere lamps simply do not deliver as much light to the eyes. If a simple light treatment is not enough for a serious depression, it is definitely time to talk with your doctor.

6.C. Delayed sleep phase

When the body clock seems to run too slow, it gets behind, and sends its signals to the body too late. Then we say the timing of the body clock is delayed past what it should be. The phase is delayed, to use the mathematical term. The symptoms of delayed sleep phase are 1) falling asleep too late, sometimes after lying in bed awake for many hours, and 2) waking up too late and having trouble getting up on time. People with delayed sleep phase typically have trouble falling asleep unless they stay up much later than they would wish to. Having gone to sleep so late, people with delayed sleep phase often oversleep and have trouble getting to work or carrying out morning activities, as if their bodies’ internal alarm clocks do not ring on time. Indeed, people with severe delayed sleep phase will sometimes sleep past noon. People with delayed sleep phase – unless they drag themselves out of bed – are often rather long sleepers, and they often have a grumpy mood or real depression.

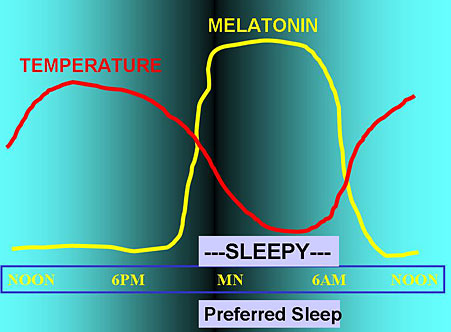

In the figure above, a normal person has the “sleepy” phase of their body clock aligned with the interval when they prefer to sleep, so they sleep well. Blood melatonin begins to rise an hour or two before sleepiness develops, and melatonin falls at about the time of awakening. Body temperature falls in the evening and during sleep, beginning to rise a couple of hours before awakening.

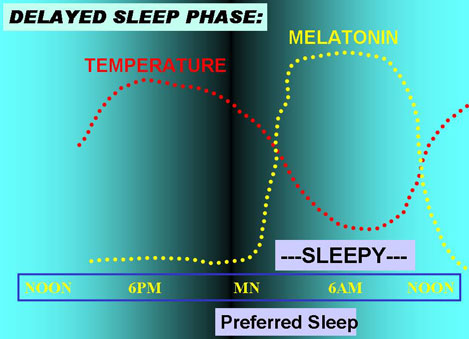

In the figure below, a person with delayed sleep phase disorder finds that the time of sleepiness does not begin until much after the time of preferred sleep onset, but sleepiness persists after the person would like to be able to get up for the day. The physiologic rhythms of melatonin and body temperature are also delayed, making it hard for the delayed person to arise at the preferred time.

Of course, when people prefer to sleep depends on school and work schedules and many social factors, and the timing of their sleepiness varies also.

People with a delayed sleep phase often feel somewhat rebellious or angry with authorities, perhaps because they have experienced so many years of people insisting that they wake up when their body clocks are telling them to keep on sleeping. Unfortunately, people who do not come to school or work on time are often regarded as lazy, so they have not received the sympathy they deserve for their body clock problems. Also, since people with delayed sleep phase may not feel very alert until well past noon, and their best and most energetic hours are sometimes past midnight, they may have learned to enjoy their habitual late activities and be reluctant to give them up for bed. Successful treatment needs a willingness to change customary habits.

The timing of sleep patterns – being advanced or delayed – does run in some families. There is evidence that people with delayed sleep phase have some genetic changes in the body clock. It is also peculiar that delayed sleep phase seems to develop somewhat late in puberty – often around 16 to 18 years of age – and be at its worst in the early 20s. College students and graduate students without fixed classes seem to be particularly prone to delayed sleep phase – there certainly isn’t much quiet in the dormitories before midnight at our university. One wonders if that rebellious trait – the wish to get out from under the thumb of authority – sometimes contributes to a delayed sleep phase. There is even some evidence in animal studies that the younger adult animals adopt a different daily activity rhythm, apparently to keep out of the way of the more dominant more mature adults. Nevertheless, we do see delayed sleep phase among mature adults and even in some elderly people.

It is apparent that too little morning light exposure has something to do with the development of delayed sleep phase. Because dawn is later in winter, we all get up later in winter because standard time causes us to set our alarm clocks an hour later than in summer daylight savings time. Of course, the dawn is earlier in the summer. A number of studies indicate that even after taking account of the time change, people tend to stay up later by the clock and get up later in winter than in summer. This trend seems to be especially prominent in northern areas (above 45° latitude), where winter nights are particularly long. In those areas, people may see no bright daylight in the morning, as they arrive at school or work before the sun comes up. Theorists have speculated that experiencing dawn is particularly important for setting our body clocks, and even, that the gradually waxing light of dawn has some special signaling significance for the body clock. In fact, MS Stephanie Rosen in my laboratory found some evidence that people who have thinner-lighter window shades (that let in more dawn light) tend to fall asleep a little more rapidly and arise a little earlier.

Whether or not the waxing light of dawn is an important signal, it is a fair bet that people whose sleep phase is delayed are not experiencing enough bright light in the morning. That is the key to treatment.

The best treatment for delayed sleep phase is to increase the dose of light that the person receives soon after their habitual awakening time. The brighter the light, the sooner after usual waking up it is experienced, and the longer the period of exposure (up to 3–4 hours), the better the result is likely to be. The problem is that delayed sleep phase is often a stubborn condition that can only be controlled by very bright light for 1–2 hours each morning. Arranging to receive that light may be hard to fit in with daily habits. I usually find that people with delayed sleep phase need one of the bright fluorescent light boxes. Although torchiere lamps and other increased lighting can be helpful, ordinary fixtures usually do not seem to be sufficient. One convenient way to get a strong dose of morning light is to use a light box (maybe a box arranged for 10,000 lux) for 30 min at breakfast time, since eating and reading the morning paper do not interfere with the benefit. For people who work at a desk, placing the light box on the desk and turning it on all morning might be effective, even if one cannot sit at the desk all of the time. If it is convenient to be exposed to bright light for several hours each morning, around 2,000 lux might well be sufficient, allowing the light box to be placed at the far side of the desk, or allowing the use of a more customary-appearing bright fluorescent or LED desk lamp.

Looking at the phase-response curve (below), we see that the best time to give bright light to somebody with delayed sleep phase is as soon after their spontaneous waking time as possible, that is, just when their natural sleepiness ends. This is a bit complicated, since at the beginning of treatment, the body's preferred waking time may be quite late in the day. It is probably best to start using the bright light after the (rather late) spontaneous waking time, and then to give the treatment earlier and earlier in the day as the person starts falling asleep earlier and waking up earlier. A really strong dose is best for the first few days of treatment to reset the body clock, so I often advise that patients start treatment on a weekend when it is practical to spend 3–4 hours outdoors right after waking up. Once a person is able to fall asleep at a reasonable hour and to awaken at the desired time (e.g., 7 am), the best time for treatment is in the early morning. In the first week or two of correcting delayed sleep phase, it is very important to use bright light treatment for a full dose every day, seven days per week.

As diagrammed above, a person with a delayed sleep phase usually also has the phase response curve delayed, and the end of the natural sleepiness time is late in the morning or even after noon. We are talking about when it is easiest biologically to sleep and then arise (e.g., on weekends), not when the person needs to arise to get to work on time. Because the body clock and its phase response curve are delayed, the best time for light to advance the body clock is also later. Moreover, as shown above, bright light early in the morning might make the delay worse. This can be a problem for delayed people who struggle to get up early to get to school or work, when the person’s phase response is still in the delay zone. For such occasions, blue-blocking orange sunglasses may be helpful outdoors to prevent light exposure on the way to work from making things worse. Once the delay in the body clock is corrected, the phase response curve will be advanced and early morning light will be helpful.

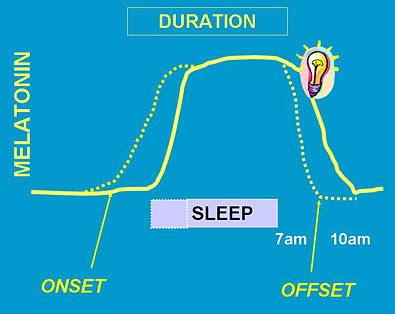

The diagram above shows how bright morning light pushes melatonin onset and offset earlier (dotted lines), so the person can get to sleep earlier.

Just as it may be hard to set an alarm clock for the proper time but easier to set the alarm to ring daily once it is set to the correct time, similarly, it takes less bright light to keep the body clock set properly, once a delayed body clock has been reset. After a delayed body clock has been successfully readjusted and the person’s habits have readjusted to the new sleep hours also, a bit less effort may be needed to keep the body clock from delaying again. Nevertheless, people with delayed sleep phase commonly relapse if they stop using light treatment loyally. Also, it is very harmful for people with delayed sleep phase to stay up late on weekend nights and to sleep late on weekends and days off. A person with delayed sleep phase should try to keep a regular wake-up time, seven days per week, because once a little relapse is permitted on days off, the person with delayed sleep phase will find it too hard to recover.

There are many ways of arranging to get added bright light in the morning, such as installing bright lighting in the bathtub or around the bathroom mirror (like the dressing-room lights of movie stars), increasing lighting in the bedroom and kitchen, and removing sunglasses when driving or walking to work. Unfortunately, in my experience, these arrangements are often insufficient for a seriously-delayed sleep phase. Difficult delayed sleep phase usually requires a fluorescent or LED light box. Spending 30–60 minutes or more outdoors in early morning daylight (after the sun comes up) should be effective. Unfortunately, winter fog and rain often make getting daylight exposures difficult even in San Diego (where I live), whereas in the coldest and hottest parts of America, getting enough morning outdoor daylight is well-nigh impossible during parts of the year. Do not depend on sitting near a window or opening curtains – it is almost never bright enough. For these reasons, I do recommend the bright light boxes for delayed sleep phase.

The theoretical importance of the dawn signal has inspired some doctors to try “dawn simulators,” which slowly increase artificial room lighting in about the same pattern that dawn might creep through a bedroom window. These doctors believe that the natural dawn signal is so powerful that it will reset the body clock even during sleep, when the light has to pass through the eyelids, and that dawn simulation does not have to be very bright. Several dawn simulators designed to mimic the light of dawn are now being sold, though they have not been tested very well. There is preliminary evidence that dawn simulators may have some benefit, although perhaps not as powerful a benefit as a 10,000-lux light box. In treating patients with SAD who tend to get up late, lighting waxing only up to 250 lux, entering through closed eyelids during sleep, did seem to reset the body clock and to partially relieve the depression.[77] Another test of administering increasing brightness through a sleep mask seemed to show some benefit.[78] It would be nice to see dawn simulators more thoroughly tested, since they may be a particularly convenient way of dealing with delayed sleep phase.

Some Japanese researchers have reported that supplemental vitamin B12 is useful for delayed sleep phase, even when the patient does not have any evidence of vitamin deficiency by the usual criteria. They recommend about 1-2 mg. (1,000µ or 1,000-2,000 micrograms) of oral vitamin B12 daily. This is much more than the minimum daily requirement which is contained in most multivitamin pills. The vitamin B12 which can be easily purchased in 1 mg. doses at North American grocery stores is a slightly different vitamin from that tested by the Japanese, but it probably makes no difference. Unfortunately, the best Japanese test of vitamin B12 for delayed sleep phase did not demonstrate any good effect. Nevertheless, since vitamin B12 in high doses has practically no known side effects and is very inexpensive, I do recommend that people with delayed sleep phase try the 1 mg dosage.

6.D. Depression and delayed sleep phase

Depression does seem to be associated with delayed sleep phase, particularly among young adults and women before menopause, and particularly when the problem occurs in the winter. Indeed, delayed sleep phase disorder and seasonal affective disorder tend to be associated (that is, comorbid). Our research group also gathered some evidence that some of the same genetic variations may cause delayed sleep phase and depression, and this has been supported by large population genetic surveys. [79] With delayed sleep phase (as with advanced sleep phase, as previously mentioned), it is often difficult to tell when the problem is a sleep timing problem and when it is a real depression, because the problems often seem mixed together. Bright light which corrects delayed sleep phase does usually seem to lift mood symptoms also. Nevertheless, as I mentioned before, if a depression is serious enough to keep you from your normal occupations and pleasures or to cause weight loss, guilt, thoughts of death, or other serious distress, let me repeat that you should talk it over with your doctor. If light treatment for delayed sleep phase does not alleviate the depressive symptoms, it is certainly time to talk with your doctor.

6.E. Melatonin and delayed sleep phase or advanced sleep phase

Melatonin is a night-signaling hormone. It is generally higher at night both among humans (and other creatures) that sleep at night, and also higher at night among rodents and other creatures that are awake and active at night and that sleep in the day. Obviously, melatonin is not primarily a sleep-inducing hormone. Melatonin has a role in coordinating circadian rhythms throughout the brain and the rest of the body, even impacting rhythms that peak at different times. As mentioned, the evening rise and morning fall of melatonin are late among “evening people” with delayed sleep phases. Probably a delayed body clock and delayed sleep tend to delay melatonin and likewise, a delayed melatonin pattern tends to delay sleep and the body clock. Conversely, the evening rise and morning fall of melatonin are early among “morning people” with advanced sleep phases. Some melatonin effects on hormone systems and mood are discussed in Chapter 9.

Taken at bedtime, melatonin has little effect in shortening time to fall asleep, though it accelerates sleep onset when taken an hour or two before bedtime. When taken by mouth, ordinary melatonin is mostly metabolized in an hour or two. As a consequence, melatonin is of little or no use for increasing total sleep at night, except among those evening people having problems with delayed sleep phase. Melatonin in very low doses (e.g., 50-500 micrograms) might be potentially useful for chronic delayed sleep phases. An extended release form of melatonin (brand name Circadin) is licensed as a prescription sleeping pill in Europe (not in the U.S. as of 2019). Tests of Circadin sponsored by its manufacturer demonstrated some usefulness and a favorable side-effect profile, but evidently the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has been skeptical of Circadin and has not licensed it. One might speculate there could have been safety concerns.

Although as much as 5% of the U.S. population has been reported to be taking melatonin, I know of very little long-term population safety data and no long-term safety trials. In my own data, although not statistically reliable, there was a trend for women with higher melatonin secretion to have shorter lives. Much larger studies are needed. It is possible that melatonin may have anti-cancer properties when taken routinely, but it is also possible that melatonin suppresses sex hormones and promotes depression.

Endnotes for Chapter 6

75. Kripke DF, Elliott JA, Youngstedt SD, Rex KM. Circadian phase response curves to light in older and young women and men. J Circadian Rhythms. 2007![]()

![]() ; 5: 4. [return]

; 5: 4. [return]

76. Youngstedt, SD et al. Light exposure, sleep quality, and depression in older adults. in Holick MF, Jung EG (eds): Biologic Effects of Light 1998. Boston, Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1999:427-435. [return]

77. Avery, DH et al. Dawn simulation and bright light in the treatment of SAD: A controlled study. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50:205-216. [return]

78. Cole, RJ et al. Bright light mask treatment of delayed sleep phase syndrome. Journal of Biological Rhythms. 2002![]()

![]() . [return]

. [return]

79. Jones SE, Lane JM, Wood AR, et al. Genome-wide association analyses of chronotype in 697,828 individuals provides insights into circadian rhythms. Nat Commun. 2019![]()

![]() ;10(1):343. [return]

;10(1):343. [return]

Table of Contents

Brighten Your Life, in all its formats, including this ebook, copyright ©1997-2019 by Daniel F. Kripke, M.D. All rights reserved.